In November 2019, the Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP) provided its first road policing training programme in Fiji with the Pacific Islands Chiefs of Police for police agencies from across the Pacific.

Elements of the training included the lifesaving benefits of vehicle passengers wearing safety belts. Each year, it’s estimated that wearing safety belts alone saves 100,000 lives a year and remains one of the single largest life saving inventions ever introduced in vehicle safety. A second issue was the risk associated with mobile phone use while driving. Drivers who talk on phones, both hands-free and hand-held, are four times more likely to be in a crash resulting in injuries.

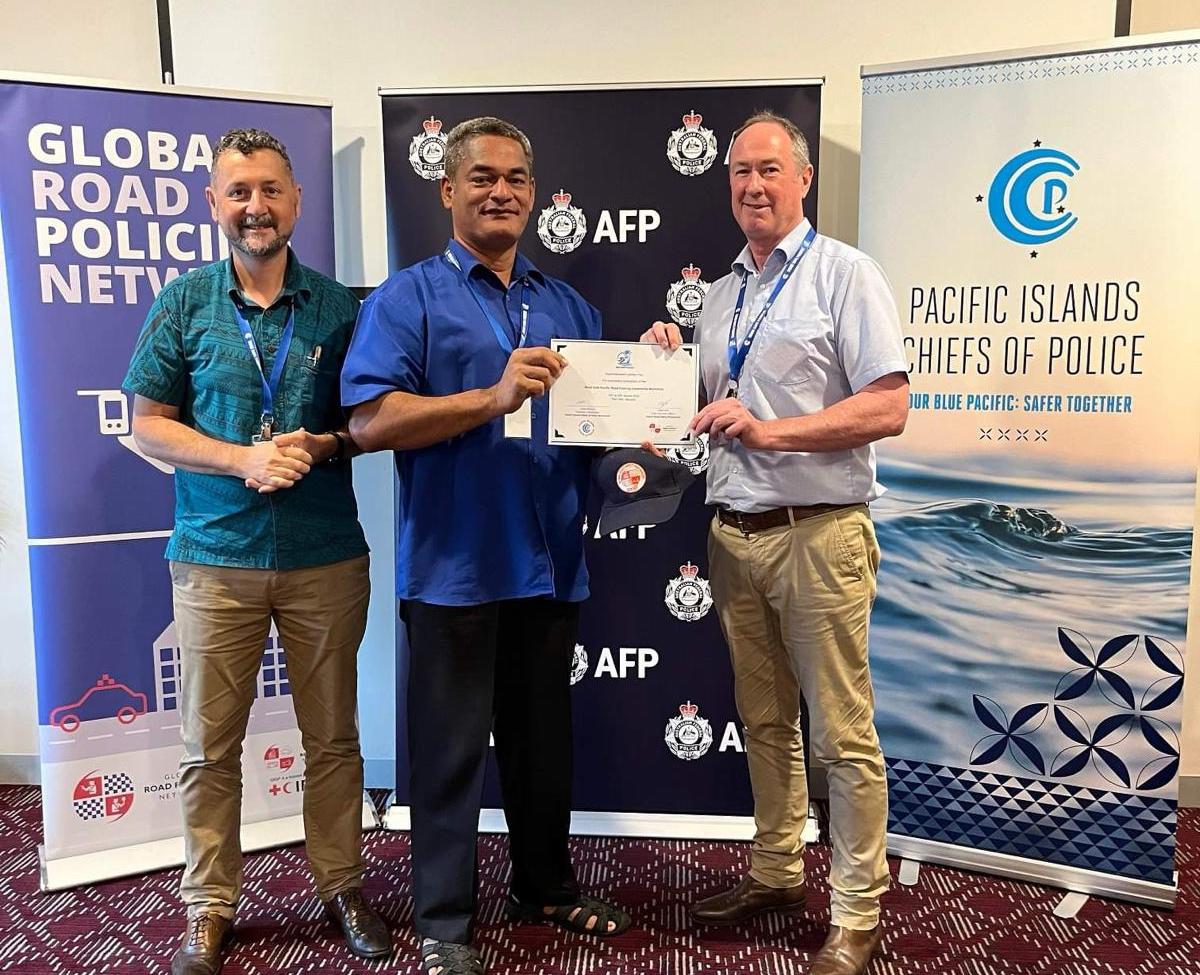

After the training finished, Superintendent Lemoto Piliu, the head of road policing for Tonga Police, took on the challenge to save lives in Tonga and successfully advocated for the introduction of safety belt use laws and a ban on the use of mobile phones while driving.

As a consequence, in 2020 a new law was introduced in Tonga requiring drivers and all front seat passengers over 12 years old to wear seat belts while driving in Tonga and a ban on the use of mobile phones while driving was also put in place.

In describing what occurred, Lemoto explained: “After returning home from Fiji in 2019, I formed a task force to develop a seat-belt campaign and one to ban the use of mobile phones while driving. We visited different communities, spoke on radio programmes and successfully had new laws introduced.”

This serves as a powerful example of how police, armed with evidence as to what works to reduce road trauma, can successfully advocate to have new life saving laws introduced. The GRSP congratulates Lemoto for his achievement!

Speed management is a fundamental component of the Safe System approach to road safety. Speed determines both the likelihood of a crash occurring and the severity of outcome. As speeds increase, so does the likelihood that any crash outcome will become more severe. It is globally recognized that even small reductions in mean vehicle travel speeds result in large reductions in trauma.

Speed management is a fundamental component of the Safe System approach to road safety. Speed determines both the likelihood of a crash occurring and the severity of outcome. As speeds increase, so does the likelihood that any crash outcome will become more severe. It is globally recognized that even small reductions in mean vehicle travel speeds result in large reductions in trauma.

There are numerous peer reviewed studies that have measured real world impacts of speed reduction. These studies tell a consistent story. As speeds reduce, so does road trauma. This basic ‘rule of thumb’ applies when calculating casualty reduction.

A 5 per cent decrease in average speed leads to approximately a 10 per cent decrease in all injury crashes and a 20 per cent decrease in fatal crashes.

In a non-divided rural road environment, where vehicles are capable of involvement in head-on collisions, speed limits of no more than 70 – 80 km/h should be in place to ensure crashes are survivable.

To further illustrate the impact of rural speed limit reduction, when the speed limit was reduced in Sweden from 90km/h to 80 km/h on a large portion (21 per cent) of the state road network (mainly undivided rural roads), the mean speed was found to have reduced by more than 3 km/h and the number of fatalities was reduced by about 40 per cent.

In a bigger sample size, in France—where speed limits on similarly undivided rural roads were reduced in 2018 from 90 km/h to 80 km/h—fatalities were reduced by 12 per cent on the relevant part of the network, with an overall reduction of 331 deaths on an annual basis compared to the previous four years.

The ETSC (European Traffic Safety Council) reported in 2019 that:

“Countries with a significantly lower road mortality rate than the European Union average of 5 deaths per 100,000 population apply a 70 or 80 km/h standard speed limit on rural, non-motorway roads.”

It is a global problem that there is a lack of understanding by members of the public about the link between mean travel speeds and trauma rates. Higher speeds are perceived to be safe because at an individual level, serious crashes are rare events. However, the science is clear that small decreases in speed when multiplied across a population, generate large decreases in road trauma.

It is a common international phenomenon that commentators will want to attribute road trauma rates solely to behaviours such as driver distraction, driver inexperience or driver education. While these issues are important, they avoid a fundamental truth. Regardless of the reason a crash occurs, impact speed almost always decides injury severity and lowering speed limits and rigorously enforcing them has globally proven to be a highly effective casualty reducing strategy.

Further, there are major consequential benefits to rural speed reduction as lower speeds will also generate fuel savings and reduce CO2 emissions.

Focusing on speed provides a major opportunity for police to drive down mean travel speeds and make a major contribution to the reduction of road trauma.

When speeds reduce, everyone wins.

Dave Cliff ONZM MStJ

CEO, Global Road Safety Partnership

I joined the Australian Federal Police (AFP) in 1998 and over the past 25 years have worked across many different areas of policing. I have had some challenging roles along the way, such as overseeing the AFP Human Source programme, working in the Organised Crime portfolio trying to combat the illicit drug trade and being a team leader in our Professional Standards Command. In October 2023, an opportunity presented to take on the role of Officer in Charge of Road Policing in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), and I can honestly say it has been the most demanding role I have ever undertaken.

I joined the Australian Federal Police (AFP) in 1998 and over the past 25 years have worked across many different areas of policing. I have had some challenging roles along the way, such as overseeing the AFP Human Source programme, working in the Organised Crime portfolio trying to combat the illicit drug trade and being a team leader in our Professional Standards Command. In October 2023, an opportunity presented to take on the role of Officer in Charge of Road Policing in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), and I can honestly say it has been the most demanding role I have ever undertaken. The ACT houses Canberra, Australia’s capital, built between Sydney and Melbourne in the early 20th century. Known as the “Bush Capital”, Canberra covers an area of just over 2,300 square kilometres and is made up of forest, farmland and nature reserves, along with urban living across a number of districts. The population of Canberra is approaching 500,000 people.

The AFP provides all policing services to the people of Canberra and this, of course, includes road policing. The portfolio includes general road policing, which is focused on road safety and enforcement, as well as major collision investigations. When I accepted the position of Officer in Charge of Road Policing, I had no real background in road safety, other than my experiences in general duties policing in the late 1990s and early 2000s. To say it was a steep learning curve would be an understatement. I had no idea that road policing would attract so much attention from so many people. In hindsight, maybe I shouldn’t have been so surprised. At the end of the day, the role of road policing is to keep people safe and work with government on initiatives and policies that are aimed at reducing fatalities and injuries on our roads.

So, what are the challenges and what does my average day or week look like? One of the main challenges is addressing driver behaviour on our roads. Canberra is lucky to have good quality road infrastructure, but with that comes the temptation of drivers to push the boundaries, especially excessive speed. We also have problems with reckless drivers using our roads and rural areas to undertake organized burnout events. They use social media to organize events and codes that correlate to certain meeting locations. This is an issue that many police jurisdictions in Australia and around the world have encountered. It’s also an issue that attracts significant feedback from the community who quite rightly have an expectation that this type of behaviour is dealt with by police.

There is also the delicate art of balancing expectations of different community groups who all utilize the roads in different ways and face different issues. Canberra has a large network of cycling paths and dedicated cycling lanes on some of our roads. The cycling paths are used by pedestrians, cyclists, electric bikes and e-scooters. This mixed use can cause dangers to users. One of the more complex issues is the interaction of bike riders on roads. The safety of vulnerable road users is an important focus for road policing, but my own observations are that perhaps in Australia, as a community, we are not as accepting of cyclists on our roads. There is an ongoing battle on social media in relation to the rights of car drivers versus the rights of cyclists to travel on the same road network.

One aspect of my role that really caught me by surprise was the ongoing media commitments. In my previous 20 plus years in the police I had little, if any, exposure to media requests. Since commencing in my role in road policing, I have faced the media on countless occasions, from joint media engagements with the ACT government on road safety campaigns to discussing ongoing road safety issues such as speeding in school zones and dangerous driving. One of the more difficult tasks is talking to the media after every fatal collision on our roads. These completely avoidable crashes cause so much devastation on families, and quite often, a slow burning effect on first responders who attend the collisions, that may simmer away for years.

However, there are positive aspects to working in this area of policing. Community engagement is something that road policing is heavily involved in. Attending schools to educate future drivers on responsible driving practices, taking our vehicles and motorcycles to community events and seeing the smiles on children’s faces when they sit on a police motorcycle or sit in a police vehicle and turn on everything and anything that lights up or makes a loud sound. Another great aspect of road policing is working with other police jurisdictions in Australia and abroad. In March this year I was lucky enough to travel to Vanuatu to participate in a Road Safe Pacific Road Policing Leadership Workshop facilitated by the Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP) and Pacific Islands Chiefs of Police. This was a great opportunity to collaborate with partners on all aspects of road safety.

Working in an area of policing that can have such an impact on the behaviour of drivers on our roads is extremely rewarding and equally challenging. It is a job where you can never afford to become complacent, just like being the driver of a motor vehicle or rider of a motorcycle.

The E-Survey of Road Users’ Attitudes (ESRA) is a joint international initiative of research organizations and road safety institutes led by the Vias Institute in Brussels, Belgium. ESRA involves more than 60 participating countries from across the world and aims to collect, analyse, and report on comparable road safety performance data and culture using a large set of road safety indicators.

These indicators provide scientific evidence to inform and guide policy making at both national and sub-national level. Starting with 17 countries in 2015, the project has grown to involve 68 participating countries from 6 continents in 2024.

The E-Survey of Road Users’ Attitudes (ESRA) is a joint international initiative of research organizations and road safety institutes led by the Vias Institute in Brussels, Belgium. ESRA involves more than 60 participating countries from across the world and aims to collect, analyse, and report on comparable road safety performance data and culture using a large set of road safety indicators.

These indicators provide scientific evidence to inform and guide policy making at both national and sub-national level. Starting with 17 countries in 2015, the project has grown to involve 68 participating countries from 6 continents in 2024.

The survey reports on self-declared behaviour, attitudes, and opinions on unsafe behaviour in traffic, enforcement experiences and support for policy measures[1].

The ESRA focuses on five key road user areas: speeding; driving under the influence of alcohol, drugs and medicines; distraction; protective systems (e.g., seat-belt/helmet use); and fatigue. It targets five main road user groups: car drivers, moped/motorcycle riders, cyclists, pedestrians, and e-scooter riders. Specific objectives of the survey include:

The ESRA is a valuable tool for understanding road safety culture and behaviour and it provides important insights that, whilst not focused solely on enforcement, can be highly informative to enforcement agencies by:

An interactive dashboard and country fact sheets are available on the ESRA website and an overview of the project and the results of all three survey editions are available here: www.esranet.eu

[1] Meesmann, U., & Wardenier, N. (2024). ESRA3 methodology. ESRA3 Thematic report Nr. 1. Version 1.0. ESRA project (E-Survey of Road users’ Attitudes). (2024 – R – 09 – EN). Vias institute. https://www.esranet.eu/storage/minisites/esra3-methodology-report.pdf

[2] https://www.esranet.eu/storage/minisites/esra2019thematicreportno6enforcementandtrafficviolations-update.pdf

In March 2024, GRSP held a three-day Road Policing Leadership Workshop in Port Vila, Vanuatu. This was the second such offering by GRSP for senior leaders and managers from participating Pacific Islands Policing Agencies, the first being held in 2019. The workshop was facilitated by the Pacific Island Chiefs of Police (PICP) Secretariat to support the PICP’s Road Safe Pacific Network and considered essential for police road safety leads to discuss shared challenges and opportunities in an effort to effect changes in unsafe driving and riding behaviour.

In March 2024, GRSP held a three-day Road Policing Leadership Workshop in Port Vila, Vanuatu. This was the second such offering by GRSP for senior leaders and managers from participating Pacific Islands Policing Agencies, the first being held in 2019.

The workshop was facilitated by the Pacific Island Chiefs of Police (PICP) Secretariat to support the PICP’s Road Safe Pacific Network and considered essential for police road safety leads to discuss shared challenges and opportunities in an effort to effect changes in unsafe driving and riding behaviour.

The workshop provided a great opportunity for participants to learn about the strong body of evidence that shows the link between improving road policing performance and reductions in road crash deaths and injuries, and to discuss and formulate strategies to reduce harm on roads across the Pacific region.

The event was formally opened by Vanuatu Police Commissioner Robson Iavaro and led by GRSP experts, with content and activities focused on addressing road safety issues relevant to Pacific Island communities. Police road safety leads represented American Samoa, Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, Nauru, New Caledonia, Palau, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, and Vanuatu. We look forward to seeing positive progress being made to improve road safety performance across the Pacific in the months and years ahead.

My name is Jason K. Young, I am a Traffic Crash Investigator assigned to the Guam Highway Patrol Division within the Guam Police Department (GPD). Guam is a Territory of the United States of America, located in Micronesia, in the Western Pacific. Guam is “Where America’s day begins”, on a 540 Km2 island with a population of 170,000.

My name is Jason K. Young, I am a Traffic Crash Investigator assigned to the Guam Highway Patrol Division within the Guam Police Department (GPD). Guam is a Territory of the United States of America, located in Micronesia, in the Western Pacific. Guam is “Where America’s day begins”, on a 540 Km2 island with a population of 170,000.

The Guam Highway Patrol Division (GHPD) has jurisdiction over the entire island. GHPD’s primary responsibilities include investigating fatal collisions, traffic violation enforcement, collision follow-ups, GPD official vehicle collisions, and agency-level training and certification of general duties police officers.

The Highway Patrol Division currently has 14 officers, 7 being investigators. As we are subject to activations for fatal collisions, a typical day is tough to nail down. We conduct enforcement as outlined in five federal programmes relative to traffic enforcement: Highway Enforcement of Action Team (HEAT), Seat-belt Child-restraint Occupant Protection Enforcement (SCOPE), Click It Or Ticket (CIOT), Driving While Impaired (DWI), and Pedestrian Safety.

Enforcement operations are regularly scheduled and completed throughout the year. In addition to federal enforcement, the Highway Patrol Division trains police officer trainees in DWI enforcement, teaching them to utilize the Standardized Field Sobriety Test (SFST), DWI checkpoint operations, traffic direction, and other areas related to the motor vehicle code.

As an officer assigned to the Highway Patrol Division, I have been assigned a take-home vehicle since I am always on call and can be activated to investigate fatal collisions 24 hours a day, seven days a week. My day begins when I enter my marked Dodge Charger sedan. Typically, the Highway Patrol begins our day at 6:00 a.m. by conducting an enforcement operation, usually speed enforcement using a Laser Tech LTI 20-20 Ultralyte speed gun. This type of operation involves the entire section. One officer will use the instrument while other officers flag vehicles into a safety zone and record all vehicles being pulled in, with the remaining officers issuing citations (infringements). This type of operation is conducted for about two hours at a time. Locations are chosen based on crash data and other intelligence-generated methods indicating where our presence will have the most significant deterrence effect while also conducting enforcement.

After conducting enforcement, I typically return to my office and review the computer system to see what happened while I was off duty. This keeps me abreast of arrests and other new cases while maintaining operational readiness. I also deal with emails and other administrative issues.

As a Traffic Crash Investigator, our investigations are very technical and require a great deal of time to complete. As each collision is unique, so is the investigation that follows. Not only do we investigate the collision itself, but we also investigate the events leading up to a fatality. We do our best to find the root cause of the collision—for example, a drunk driver involved in a fatal crash. We will determine where they were drinking, how much they drank, and if this overconsumption was a regular occurrence or if they had some sort of triggering event that caused them to overconsume alcohol. At the scene of a collision, we investigate in detail so that we can present our findings to give the families closure or present evidence in court to prove beyond any reasonable doubt that a suspect is responsible for the crash. This requires meticulous reports completed in several steps as the investigation progresses and develops.

If I am not at my office writing reports, I have other duties. These can span from maintaining the breath testing apparatus for determining the blood alcohol content of suspected drunk drivers to moving and maintaining speed radar trailers used to collect speed data.

Continuing education training and other administrative items are also part of my day. I am finishing my university degree and attending college classes during the week, for which I take about two hours off to attend courses held during the day. Thankfully, I have some flexibility with my university schedule, and most classes occur in the early evening after my working hours.

I spend as much time with my wife and two children as possible during evenings and weekends. My son and daughter are seven and five, respectively. While they understand that I have an important job, they want as much attention as I can give them. I prioritize things like picking them up from school and reading to them before bed every night.

Officers of the GHPD are empowered to conduct enforcement at their discretion. They will typically spend the last few hours of the day patrolling the island, conducting speed enforcement and any other violation of the motor vehicle code around the island individually. If a fatal collision has recently occurred, a typical afternoon would include returning to the scene during daylight hours. Fatal crashes tend to happen at night and require us to return later for photographs, measurements, and canvas for camera footage, among other tasks. All vehicles involved in fatal collisions are impounded and stored by GPD during our investigations to allow for further examination as the investigation progresses.

I will then make my way toward my residence as my shift ends and deal with anything that comes along the way. Only once I arrive at my home does my shift end. I will conduct a final check of my vehicle and wash it if required, at which point I can finally end my day, usually around 4:30 p.m., so I can pick up my kids from school.

Finally, at half past ten, I can settle down and get some sleep. But no, my phone rings, and police dispatch informs me that I am being activated for a fatal collision with a suspected drunk driver and another vehicle at a major intersection. Even though I’ve had a long day, fifteen minutes later I am back in the car, en route to the crash scene.

Dear Colleagues,

Dr Helen Wells (Director of the Roads Policing Academic Network – RPAN) is currently completing an 18-month Fellowship at the UK Home Office, exploring the implications of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs) for policing. Her work is focusing on the physical frontline implications of CAVs being driven by the public and within the police fleet itself, rather than the digital forensics/investigation side of the topic (which others are exploring).

She is seeking expert input on the issue from across the policing landscape internationally. If you would like to speak to Dr Wells, please contact her at h.m.wells@keele.ac.uk. Likewise, if you would like to know more about RPAN, Helen will be pleased to hear from you.

Wishing you all my very best,

Dave Cliff ONZM MStJ

CEO, Global Road Safety Partnership